n a life’s journey that has been strewn with more than its share of potholes, bumps and barriers, Jorge Chinea, professor of history and director of Wayne State University’s Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS), has less dodged the obstacles in his path than powered through them.

Rising from an adolescence mired in poverty in semi-rural Puerto Rico to a youth in New York marked first by gang life and, later, by passionate political activism, Chinea has undergone remarkable change with each step of a journey that has earned him a place as a respected pillar for social justice in Detroit and as one of the most prominent voices for the city’s Latino community.

“Joining gangs was the last thing I wanted to do, but I had four younger siblings and a divorced mother whom I needed to protect, so I entered that world reluctantly, hoping to deter ill-intentioned people from messing with them,” Chinea recalled. “In the course of gang-banging, I learned that these groups were not all the same, and eventually helped organize one, the Renigades of Harlem, that banned heavy drug use and promoted the rehabilitation of abandoned buildings. That move changed my life for the better.”

From his current post as head of CLLAS, Chinea the historian provides a critical look back on academic topics such as the history of Latin America and the impact of the slave trade on the Caribbean, but the longtime social justice warrior is just as likely to be enmeshed in work in southwest Detroit — traditional home to the city’s Latino community — that touches on contemporary hot-button issues such as diversity, racial disparities and immigration.

“I came to Detroit because back in 1983, one of the faculty members of my doctoral committee at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Dennis Valdes, began telling me about his experiences as a professor of the Center for Chicano-Boricua Studies, and talked highly about the program’s community roots,” Chinea said. “Based on what I heard, I knew then that I had to be part of that program.”

Since arriving in Detroit in 1996, Chinea said he’s endeavored to keep the spirit of the center alive and active in the community, making himself available to address a number of subjects — especially education, immigration, community development — and to otherwise collaborate with nonprofit agencies, civic groups, local schools and even businesses seeking to enhance cultural awareness within their ranks.

He is currently involved with the Michigan Hispanic Collaborative’s mission of fostering postsecondary educational access with the support of several other partners, especially the DTE Energy Foundation.

This summer, weeks ahead of the start of National Hispanic Heritage Month (which runs from Sept. 15 to Oct. 15), the Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies announced that it had begun accepting contributions for an endowned scholarship in his name that would provide opportunities to underrepresented students at Wayne State. The scholarship will be awarded to a student earning a minor in Latino/a and Latin American Studies while maintaining at least a 2.5 GPA. Preference will be given to students with a demonstrated commitment to community service/engagement.

His sojourn began on the northern coast of Puerto Rico, in the town of Toa Alta, where he was born. Not long after his birth, Chinea and his family moved in with his grandfather, who worked as a sugarcane field worker just south of San Juan.

“We were very poor,” recalled Chinea, now age 66. “Every month, a U.S. Army Jeep would drop off a bag — like the size of a duffle bag — of surplus food staples. We had to make it on that and what income my mother would receive through her factory job and other government assistance.”

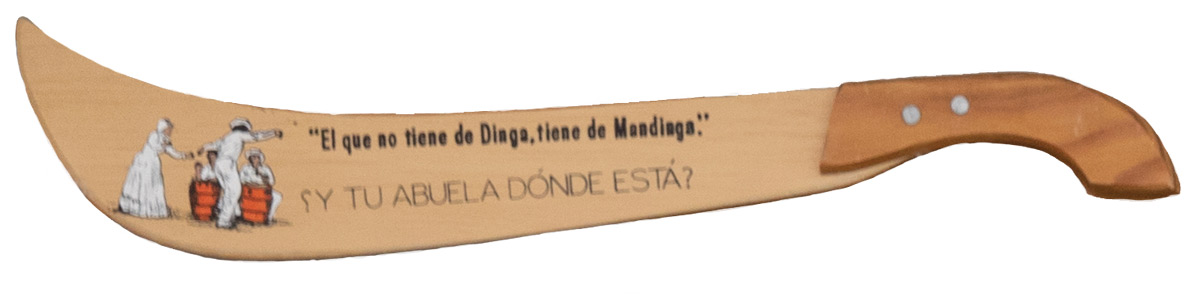

Living with his grandfather, a young Chinea learned early how to survive daunting challenges, including having enough food on the table to help feed his mother and four siblings. “I would gather my landscaping tools, a rake, wheelbarrow and machete, and go to the wealthier neighborhoods offering to clean up their yards of tough weeds and perform basic landscaping duties,” he said. I also was a “shoe-shine boy…doing lots of jobs” to help us get by.

In 1967, following years of Chinea’s family grappling with crippling poverty, a friend invited them to move to New York City’s Spanish Harlem neighborhood. But before the family made any final decisions, Chinea recalled, he was approached by his mother — who asked her then-13-year-old son to first agree to the relocation.

“My mother asked for my consent since I was the oldest son,” Chinea recalled with a smile. “This is a cultural standard, consulting with the eldest male of the family. This made me feel empowered. But later I learned from my older sister that she actually was asked for consent before me. This revelation was reassuring because my sister has held great responsibilities within our family unit.”

The move to New York brought new hurdles for the family to clear. Chinea recalled the language barrier posing a particularly tough challenge for him. “Because I could not speak English, I was placed in a special class for non-English-speaking students. And, I was pushed back to the seventh grade. In Puerto Rico, I was an honor student in the ninth grade. This was disheartening.”

Chinea endured bullying and taunting from English-speaking kids. “It was embarrassing for me, not being proficient in English,” he said. “And the academics were very difficult because of my deficiencies in the language. Rather than studying and making an effort, I skipped classes; played a lot of stickball, handball and baseball; and hung around the gangs.”

Chinea decided to give education one more shot in the ninth grade when he joined a college-oriented program that emphasized the sciences. However, the language barrier, lack of lunch money, and a 51-block walk to school that loomed whenever public transportation wasn’t possible proved to be too much to handle. Chinea dropped out of school and took a job manufacturing maternity clothing. “I became a dues-paying member of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, 1199,” he said. “Since then, I read somewhere that Martin Luther King had high regards for this local chapter.”

Gang activity was heavy in Spanish Harlem then, and the lure for Chinea was overwhelming. “I learned quickly that living in such a diverse area that is marked by poverty, you need to join a gang for protection, companionship and solidarity,” Chinea said. So, in 1968, Chinea joined one of the biggest gangs in Spanish Harlem, the Satan Spades.

The next few years saw Chinea drift through membership in other gangs as he searched for one that promoted positive change. “It seemed that most of the gangs were spending their time fighting for their turfs, moving from one battle to the next in an effort to mark their territories. So, around 1971, I moved on to a socially conscious gang called the Renegades of Harlem as one of its founding members.”

Chinea said that growing up in the late 1960s made him keenly aware of social causes and civil rights. “It just clicked for me, this idea of social consciousness and causes, as I watched and participated in the protests and unrest around the city.”

Chinea said the Renegades tried to emulate the Young Lords — a former Chicago street gang that transitioned into a militant political party — by leaning on landlords who took residents’ rental fees but provided bad plumbing or no heat. The group also rehabilitated dilapidated buildings before they were torn down.

“I really felt that we were making a positive difference,” said Chinea. And the work also made a positive difference in Chinea’s life. He restarted his education during that period, completing his GED on his second try in 1974 after failing the first test by one point.

Then he decided to enroll at Bronx Community College and, from there, set his sights on the State University of New York (SUNY). But when he spoke to a counselor about his desire to attend SUNY, he was told not to waste his time, that he would not qualify academically to be admitted to the SUNY system — that SUNY was for “smart kids.”

Undeterred, Chinea applied to five SUNY campuses — and was accepted at all of them. He chose to attend SUNY-Binghamton, where he completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees with honors in Latin American and Caribbean studies and a double major in psychology. He also found time to get married to his wife, Terri, whom he met at Binghamton.

Chinea’s academic career went on the fast track after receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. He landed at Wayne State University’s history department and the Center for Chicano-Boricua Studies (now known as CLLAS) in 1996. In 2003, he was appointed director of the center.

The Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies, which was founded in 1971 as the Latinos en Marcha Leadership Training Program, is one of the oldest programs of its kind regionally and in the nation. It grew out of the civil rights movement, when several ethnic groups that had been marginalized demanded equitable access to formal education in order to improve their social, economic and political participation in our society. Today, the center continues to honor its mission by promoting diversity within and outside academia, and contributing its share to foster a harmonious and inclusive world for all.

“It certainly has been a ride,” Chinea said referring to his life from the humble beginnings in Puerto Rico to his achievements in academia. “I can’t imagine my life without having the experiences growing up in Puerto Rico and New York City’s Spanish Harlem.”

Among Chinea’s many notable awards, publications and scholarly achievements, he is particularly fond of his appointment as a Library of Congress Resident Scholar, a recognition that he says, “is still difficult for a young shoeshine boy from Toa Alta to comprehend.”