A New Direction

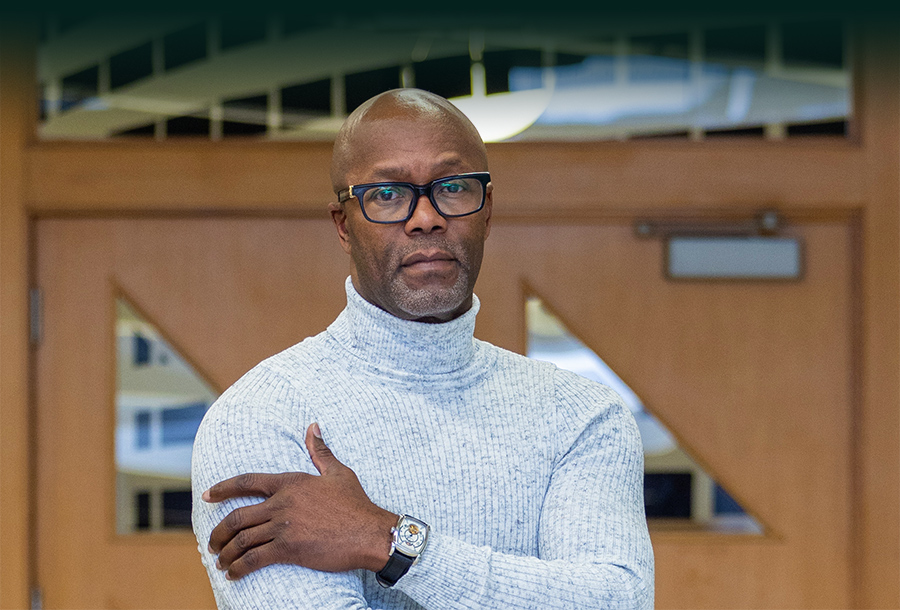

When Terrell Topps walked out of Michigan’s Deerfield Correctional Center a free man 18 years ago, he vowed he’d never go back to prison.

Before being convicted of second-degree murder in 1989 after he fatally shot a man who’d broken into his grandmother’s Detroit home and assaulted her, Topps was a talented illustrator pursuing his bachelor’s in interior architecture at Wayne State. In one fateful moment during his sophomore year, his entire life was upended, his dreams turned to ash. So, when he was finally released after nearly two decades, all he wanted to do was piece together the future he once feared was lost to him forever. For him, that meant never again going near those barbed-wired fences and 40-foot-brick walls.

“I said I’d never return,” he recalls, leaning forward on a table at a Chinese food restaurant inside the Student Center Building to emphasize his point. “I was going to get the degree I’d missed out on, and I was going to rebuild my life. I was never going back to a prison again.”

These days, however, Topps finds himself inside a prison nearly once a week.

As one of the people helming Wayne State’s Educational Transition Coordination (ETC) Program (see story on page 16), Topps uses his past experiences behind bars as well as his education — which includes a master’s in social work from Wayne State — to help currently incarcerated men and women enroll in college upon their release. Although the initiative is overseen by the university’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Topps notes that the program’s aim isn’t necessarily to turn applicants into WSU students, but rather to get them into the most appropriate school for them — be that community college, trade school or another university. To that end, he travels weekly to correctional facilities around the state to meet with incarcerated men and women who are within 18 months of release and share information about courses, colleges and careers to consider once on the outside. The work, he says, is personal, intense and holistic.

“The closer that they are to release, the more focused we become with them,” Topps explains. “In a nutshell, we take their hand and navigate their transition period. Just this morning, I had a meeting with a potential client. We were talking to him about what the FAFSA [Free Application for Federal Student Aid] is, what the MTA [Michigan Transfer Agreement] is, what financial aid and financial literacy look like, what credits transfer over to different universities and/or community colleges, and when your FAFSA application is due. We navigate all those educational to-dos in addition to helping navigate these men into community resources that they need.”

Stephanie Hartwell, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, calls the initiative “critical.” “And the preliminary stats confirm its impact,” she adds. “We have made contact and completed needs assessments on over 200 individuals. So far, 15 students completed applications to WSU and community colleges. Six of them have been admitted to Wayne State.”

Hartwell says Topps has been essential to the program’s early success. “Terrell and his team identify barriers to their success and work with the men to overcome these challenges, including but not limited to computer literacy, housing, mental health support and transportation,” she explains. “The wonderful thing about the program is Terrell actually does the work to help this pipeline of students be successful.”

Survival and stability

Sometimes, Topps says, the most time-consuming part of his job reaches beyond college campuses and prison walls, as the ETC focuses almost as much energy on helping clients address basic survival needs once they’re released as it does on helping them enroll in school. In fact, as soon as the ETC begins reaching out to its targets — most of whom contact the program on their own — it conducts a needs assessment for each to help reduce the amount of turbulence they’ll face when returning to society. Depending on the outcome of the assessment, the ETC team often must help participants secure housing, jobs, health services and other resources long before they start filling out a college admissions application.

“Bottom line is, if you’re just coming home, you need to work and you need some place to stay,” Topps points out. “When you’re released, you might need transportation just to get home. So, we navigate them to community resources that can give them those things. Education is completely secondary to your basic needs. Do we want you at Wayne State? Yes. But we want you stable — because if you come home and you are not stable, you might resort to what could get you put back in prison. We don’t want that. So, if you need a place to stay, we find organizations that can aid you with shelter. If you need a job, we look for hiring agencies that are ‘felony friendly.’ We send you to mental health services that are free or low cost. We need to be able to send you to places that can get you your vital documents. If you need an expungement process started, we plug you into agencies that can aid you in removing things from your record that might prevent you from getting hired.”

–Terrell Topps

Topps says that there are currently 20 men from various state prisons in the program, including those who are applying to attend Wayne State. (While the program is open to women, he says that there is intentional focus on men right now.) He hopes the first of this group will be able to attend WSU by January — although his hope is tempered both by caution and a desire to shield his clients from the suspicion and unfair judgement that often hounds the formerly incarcerated.

“I have to be very careful with how I present the ETC Program to other programs,” he says. “Students can Google anything, so I have to be careful with protecting the psychology of the students that I deal with. Many of them have this idea that ‘everybody knows that I was locked up.’ It’s a scarlet letter syndrome. That’s traumatic sometimes. And it depends upon your crime type. So, if you have, for example, a criminal sexual conduct crime, it’s really frowned on. I understand that, so I have to be careful with how I interact with other programs. I have to be very transparent, but I also have to understand that one program’s population and my population might be oil and water.”

To better combat misperceptions about his clients, Topps says he’s also careful about the language that’s often used to describe or define the formerly incarcerated. For instance, he says, not only does he reject terms like “inmate” as accurate descriptors, but he also eschews using the term “returning citizen,” even though it is regarded as a politically correct euphemism among many who fight against mass incarceration. Instead, he refers to them as the “justice impacted.”

“When I’ve spoken with clients, I never call them a returning citizen, ever — even though I know it’s been embraced as a correct term,” he says emphatically. “Having myself been labeled that, my pushback is this: ‘Returning citizen’ has the connotation of having been incarcerated, regardless of whether they were innocent or guilty. It doesn’t account for the fact that we also have exonerees who are students at Wayne State. They were impacted by the system even though they hadn’t done anything wrong. Also, where are these people returning from? When I think about returning citizens, I think about our veterans that go off overseas and then come back. But we don’t look at our veterans the way that we will look at a ‘returning citizen.’ And that’s rightly so — yet technically, where are you returning from? I was always in the state of Michigan and in the United States, even during my incarceration. I tell people in a minute, ‘I am not asking you to overlook my crime. I am not asking that. I am asking for fairness.’ Treat me the way you would want to be treated. Don’t just shut the door because I have lived experience with the criminal justice system. And that’s why it’s so important for me to change that narrative of language. Justice impacted. You never know what caused a person to be impacted by the justice system.”

The battle to refine language, he says, is part of the struggle to help these individuals grapple with the suspicion, the doubt and the fear that can follow those who’ve been incarcerated. Topps says this is a battle that he himself fought — and won — long ago: “I’m 18 years removed from being in prison, 33 years removed from my crime, so I’m good with whatever stigma that brings because it’s not me. That’s your perception, not mine.”

Topps says he won’t be defined by the crime he committed three decades ago — but neither will he deny it nor diminish it.

A fateful decision

He was young back then, a 1985 graduate of Detroit Kettering High School and a fresh-faced enrollee at Wayne State with dreams of becoming an architect. Growing up on the city’s east side during the height of the nation’s crack cocaine epidemic, Topps was raised largely by his maternal grandparents. With their firm guidance, he says, he’d managed to avoid a lot of the bloodshed and the misery that had begun to grip his neighborhood and others like it.

But, in 1988, both showed up at his front door.

“I was living with my grandmother at the time I was in school,” he recalls. “And some guy literally broke into her home, injured her. I wasn’t home when it happened, but I was about 30 minutes away. My grandmother had the type of home in the neighborhood that was that house that everybody went to, so everyone in the neighborhood knew her. When I got the phone call and then got to my grandmother’s house, the whole neighborhood knew exactly who’d broken in.”

The culprit, Topps says, was another young man who lived only three doors away.

“First, I had my grandmother taken to the hospital,” he says. “Then I left our home, and I went to his home. And, regrettably, I ended up taking his life.”

In the end, Topps was convicted of second-degree murder and was sentenced to 17 to 30 years in prison. During his incarceration, he spent time in at least eight prisons, including state facilities in Jackson, Ionia, Marquette and Detroit. Some stretches lasted only months; others, years. Topps admits that he was transferred often because prison officials were wary of him.

“I was a problem child inmate because of my intellect and my ability to lead,” he says. “I wasn’t a problem physically, but I had the ability to gather a group of men that could move the crowd. I was oftentimes a threat to the administration in that respect. So, I would get transferred every couple of years. Sometimes within a couple of months it would be like, ‘OK, get rid of him.’”

But for all he endured, Topps says that incarceration marked the “life-saving chapter of my life.”

“It’s where I learned how to self-assess and figure out why I was even there,” he says. “I knew the act that led me to being here. But I had to understand the decision-making that had led me to that act. And that’s what was life-saving for me, because it made me realize that a lot of my maladaptive decision-making was straight from my upbringing in my neighborhood, in my household, and around some of the men and women that I’d grown up under.”

Topps says that, growing up, he’d learned almost casually to meet affronts with violence. If, for instance, someone did something as minor as step on your new shoes at a house party, you fought them. There wasn’t much else to consider then, he says.

“It was almost mathematical,” he says. “I’m at the party. You step on my shoes, I’m going to fight. It was like two plus two.”

But behind bars, Topps began to dissect his thought processes and soon realized how much toxicity was embedded in his perspective. He began to change his thinking, his approach and, in due time, himself. He steered clear of trouble during most of his time behind bars and, after a while, earned a reputation as an inmate who could forestall trouble and organize peaceful, educational programs. He became, as he says, “an asset more than a liability.”

Even so, Topps confesses that, when he went before the parole board for an hourlong hearing in 2003, he assumed he would be summarily denied. “My thinking was, ‘I’m here for violence so they’re going to pass me over,’” he says. In fact, he was so skeptical that, when the counselor in his prison unit handed him the parole board’s written response, he didn’t even bother to read it at first.

“I was on the way out to the yard to go have activities when I got it,” he says. “I just threw the response on my bunk. I felt that that was a rejection, so I’d read that bad news when I get back. I go out and I do whatever I did on the yard. I come back, and I still don’t read it because I’m like, ‘I ain’t in no rush to get to bad news.’”

Topps says it wasn’t until the following day that he finally read the letter, thinking, “OK, let me go and deal with this bad news.”

When he finally pored over the letter, he was stunned at first, almost confused: “I read it and was like ‘what?’” He read the letter again. Joy kicked in. His parole had been approved. Topps learned he would be released in 2004.

He immediately called his grandfather — who had vowed that he’d still support his grandson but would never go to see him in prison — to tell him he’d be coming home. A week later, his grandfather came to visit so that they could figure out Topps’ release plan together.

“I immediately planned to go back to school because I knew that that’s where I belonged,” he says. “There was never a question about it.”

The comeback

When he finally got out in March 2004, Topps hit the ground running, picking up his life at the point where it’d been derailed. He started taking classes at Oakland Community College. But instead of pursuing architecture, Topps had decided that he wanted to help formerly incarcerated people turn their lives around same as he had. After earning his associate degree in mental health, he worked his way to a B.A. in psychology and social work from Oakland University in 2014. He then returned to Wayne State as part of the advanced standing social work program and, in 2016, received his M.S.W.

“When I first started back, I had to deal with feeling like everybody knows I was incarcerated, so I understand when my clients tell me that,” he says. “I absolutely had that mindset and had to work through it. So, when I try to create learning communities for the men who will be here on campus, I understand that psychology and what their struggles are going to be.”

During the time immediately after his release, he also landed a job with a company that processed legal documents and he fathered a child (he and his wife had married in 2003, just before his release, and welcomed their son, Dorian, in 2004). After graduating from Wayne State, he opened his own counseling business, Toppside Counseling, frustrated at being passed over for counseling jobs because of his criminal history.

“I opened up the counseling business because I knew that’s really where I’m going to be,” he says. “But as I’m getting there, I was at that place where we get as people, where I was being told ‘no’ by organizations and institutions because of my felony background. I got it. I understood it —but I’m not going to keep being told no. I’m going to make my yes. So, I did my own thing. I’m going to get my own counseling business. And that’s where I went with it.”

But he still wanted to do more. That opportunity would come a few years later when one of his former graduate school professors, Takisha Lashore, passed his name along to newly minted WSU deans Hartwell and Sheryl Kubiak in the School of Social Work, who had arrived on campus vowing to amplify the importance of social justice work in their respective schools. As part of their mission, Hartwell and Kubiak were seeking innovative ways to stanch the traumatizing flow of the “school-to-prison pipeline” that saps poor communities in Detroit and elsewhere. With the ETC, they’d decided to try to reverse that current instead, creating a “prison-to-school” pipeline of sorts that would offer incarcerated Michiganders an opportunity to redeem their lives through education upon their release. Now, the WSU deans needed someone to open that pipeline.

They found their man in Topps, who was an immediate hit with both Hartwell and Kubiak in his interviews. In December 2021, he was offered the job as head coordinator of the ETC Program.

“Terrell is a passionate and committed advocate,” says Kubiak. “He exemplifies what it means to be a social worker, helping individuals while simultaneously changing larger systems. He reminds us that no one should be reduced to an action on what was likely the worst day of their lives.”

Topps says the new job was as a much milestone as stepping stone.

“When I received the letter offering me the position, it had been 33 years to the day that I had committed the crime that I was locked up for,” he says. “Thirty-three years. To the exact day. Now, I’m back on campus after starting out here. And after saying I’d never return to prison, I’m in a position of employment where I am literally going back into a prison all the time. I’m going back to prison because of my education and to show these men how education can change your life.

“Now, that is what I call full circle.”